ANYA

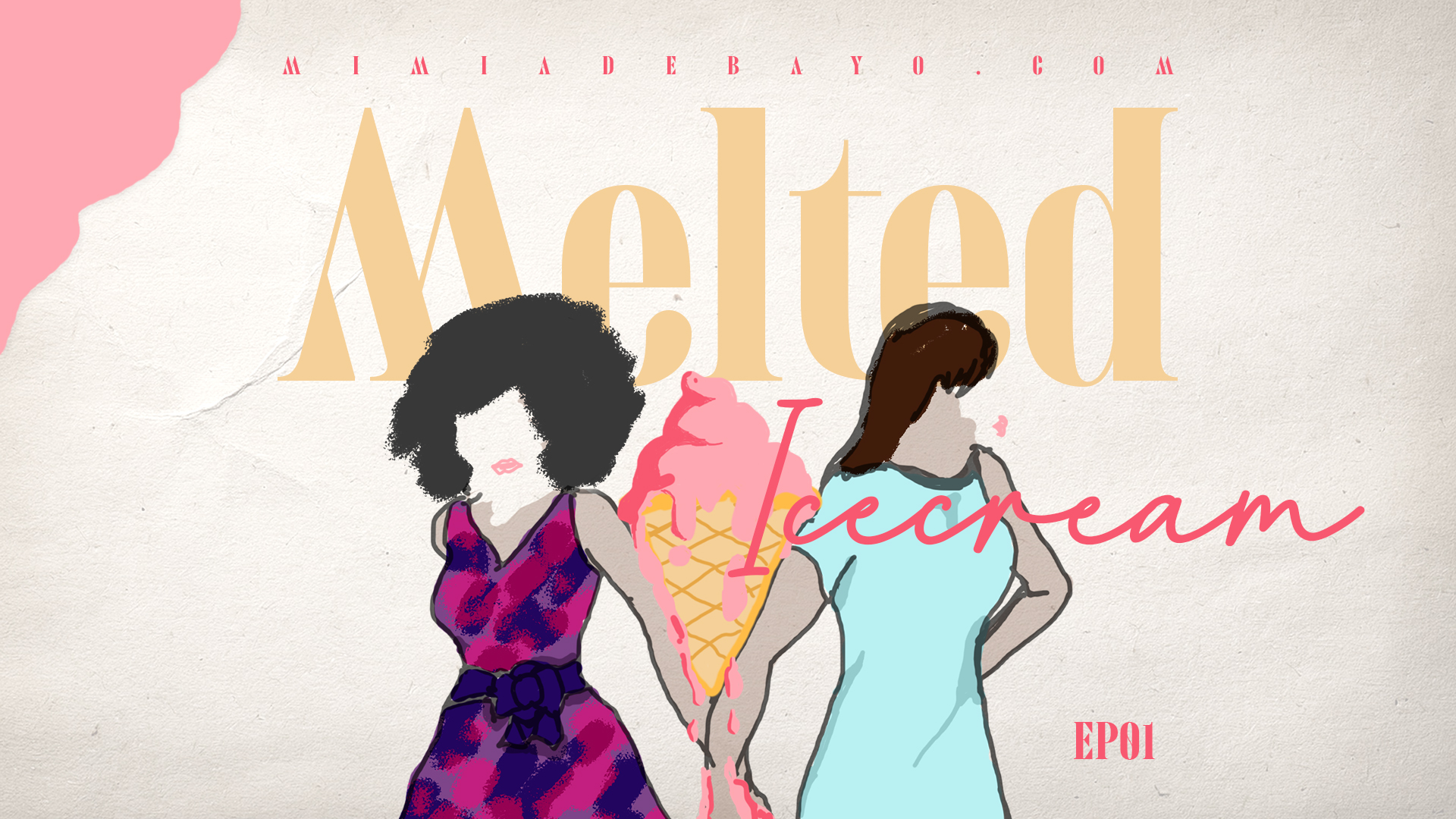

Our friendship always felt lopsided, like an ice cream cone melting unevenly—one side a puddle, the other still standing tall. I was always on the melted side, the side that dripped down your hand and left you sticky and scrambling. That meant I never had the upper hand. I was the one who needed help, the one who had meltdowns and needed consoling, the one who always needed to borrow money “just for a bit.”

Honestly, I didn’t mind it. I liked the rhythm we had, and I loved benefiting from our friendship. I thought Toria felt the same way, that it worked for her too. I remember reading a book about friendships once. It talked about auditing relationships like financial statements, asking yourself what you brought to the table. I stopped reading when I got to that part because it made me uncomfortable—angry, even. Why did everything have to be so transactional? Why turn friendships and love into formal negotiations?

When you attended job interviews, they wanted to know what you brought to the table. They asked you where you saw yourself in five years, and that was fine—expected, even. But why bring those questions into platonic or romantic relationships?

I hated the world sometimes, and what it was becoming. Why couldn’t things just be easy? Why couldn’t you be friends with someone simply because they made you feel good about yourself? Why couldn’t I be the melty part of the ice cream without feeling like I owed someone something?

I was lazy. All my childhood, I’d heard it said about me. My mom said it because I wanted to spend Christmas visiting family instead of staying home to cook. My dad said it because I didn’t study enough and came home with report cards streaked in red. My first boyfriend, Toluwani, said dating me felt like pushing a car with a dead engine—too much work for too little reward.

It took me two days for his words to marinade and for me to feel some sort of outrage about it. That’s when I broke up with him.

At work, my boss, a man with a brain as big as his stomach who talked about marketing like he was preaching the gospel, once asked me what I was passionate about.

“Are you passionate about anything at all?” he asked.

“I’m passionate about my job, sir,” I said, when really, I spent the entire workday dreaming of when I would clock out for the day.

“You don’t know what passion is,” he said. “Passion shows. It should be in your eyes, on your lips, everywhere.”

“Sir.” I had nothing more to say.

“You can’t fake it.” He shook his head.

I quit two weeks later because well, he was right, I didn’t want to spend the rest of my life convincing people to buy stuff I didn’t care about.

When I told my mom, her disappointment burned through the phone line.

“It seems the only thing you’re passionate about is quitting,” she said.

She was right, too, but I rolled my eyes anyway. I wouldn’t have called her if I didn’t need money, but that was the day she decided she wouldn’t give me anymore.

“You’re twenty-four years old,” my mother said. “Get your act together.”

“Mummy, you can’t do that.”

“I can and I am. I don’t know what I did to raise such a lazy, entitled human but it stops now.”

I screamed at the walls in my one-bedroom apartment when my mother hung up the phone. My parents weren’t wealthy, but neither were they poor. My brother and I had attended some of the top schools in Lagos and had worn second-hand designer clothing that our Aunt who lived in London sent across. I couldn’t relate to people who said they had to share one meat as a family because I had always had my own meat in my soup.

When I met Toria, it was during one of those dry spells, after I quit my marketing job and started “influencing.” Influencing was harder than it looked. I had to think up content, carve out a niche, and nothing was working. That’s why I signed up for a free Instagram course, The ABCs of Influencing.

In class, Toria stood out immediately. Her questions were sharp and useful, the kind that made you wonder how she thought of them.

During the lunch break (when actual lunch wasn’t served), I ran into her in the bathroom. She stood at the sink, reapplying her lipstick, her wig smooth and flawless. She smelled like expensive perfume and her shoes? Designer.

I might have been lazy about other things, but I was always able to spot someone with money and Toria reeked of wealth.

For the first time in forever, I was motivated. I wanted to become her friend.

“I love your hair,” I gushed over Toria, standing beside her in front of the sink. “Where is it from? I can never find the right hair vendor.” My wig was a Black Friday purchase made a year ago.

Toria glanced at me in the mirror and smiled, the kind of smile that didn’t reach her eyes but still felt polite. “Oh, I have a vendor who sources from Vietnam.”

That confirmed my suspicions: Toria was rich rich.

“So, how are you finding the class? By the way, I thought your questions were brilliant.” I said, angling for more conversation.

Again, that smile. “Thank you.”

Even though I didn’t mind the apathy that accompanied the way I moved through life, I had an uncanny sense for reading people and in that short interaction in the bathroom, I could sense that Toria was not used to being complimented.

“I’m Anya. And I think you and I are going to make great friends,” I stretched out my hand with an exaggerated flourish. I might be lazy and passionless, but I was also confident and bold.

“Anya? That’s an unusual name.”

“It’s actually Ifunanya, but my friends call me Anya.”

“And we are about to be friends, I suppose?”

“Absolutely,” I beamed.

Toria laughed. “I’m Victoria, but my friends call me Toria.”

“Nice to meet you, Toria,”our hands met in a tentative handshake.

****

That was nearly five years ago. Now, something was threatening to upend our friendship: Toria was getting married.

For five years, we’d been inseparable. Toria had slowly become my world and both of us appreciated the dynamic. Because of Toria, I could walk out of any job I felt wasn’t worth my time. Because of Toria, I didn’t invest much in romantic relationships. She was my bank, my emotional rock, the one who paid for every course I wanted to take but never finished. She made it easy to quit jobs, to avoid relationships with men who weren’t rich enough. We had an unspoken understanding – the melted ice cream understanding.

I wanted a man as rich as Toria and if he wasn’t, there was no need to expend energy on love. I had been right about Toria’s home situation: her parents had spent a lot of time outside their house than they had in it. Toria was the only girl with two older brothers who also preferred their company to hers so it seemed like Toria had had quite the lonely childhood. I believed my role in Toria’s life was to bring the companionship and drama that she had been bereft of most of her life. It was the easiest thing I’d ever done.

It worked—until Toria fell in love and decided to marry the guy.